Mosquitoes

WHO DO WE CALL MOSQUITOES?

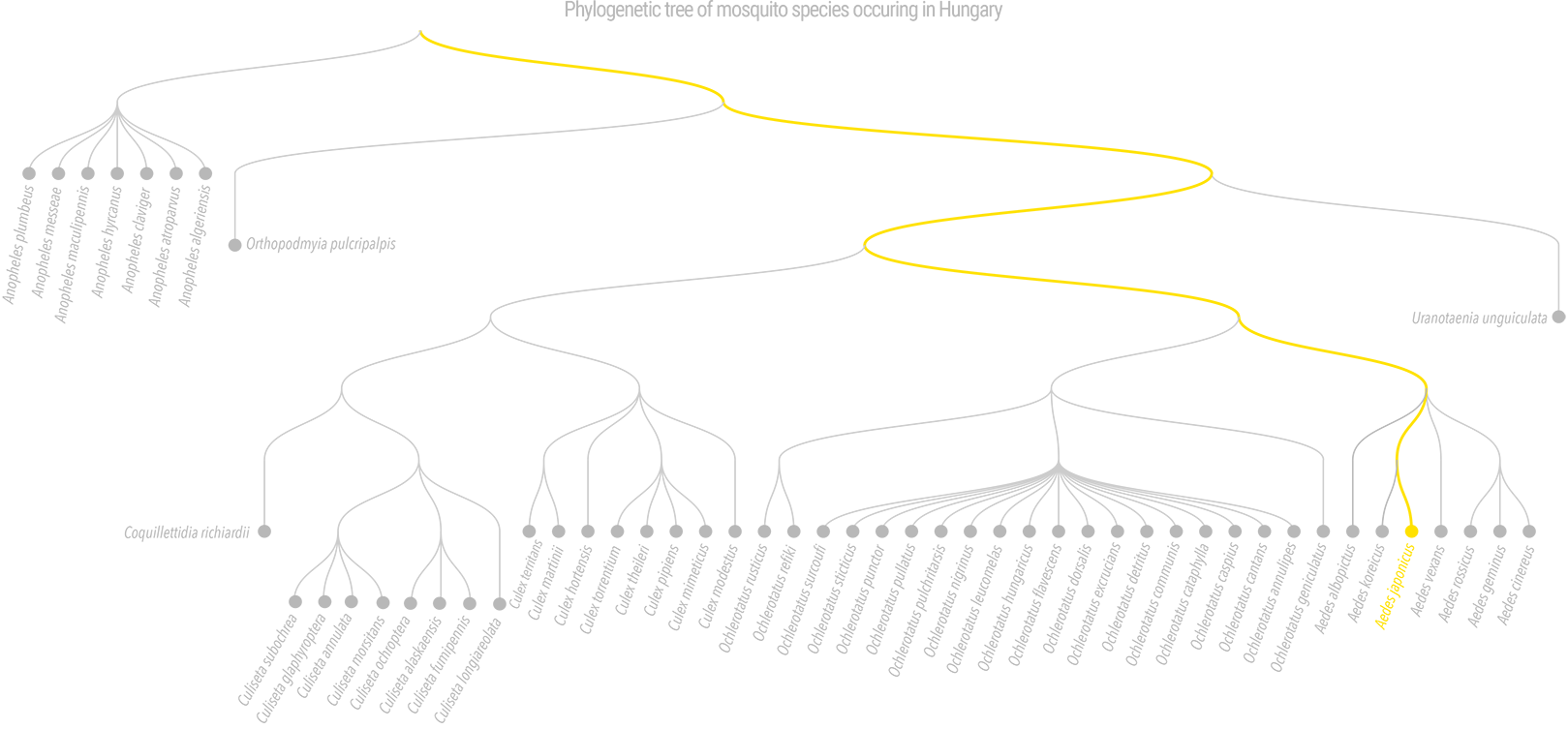

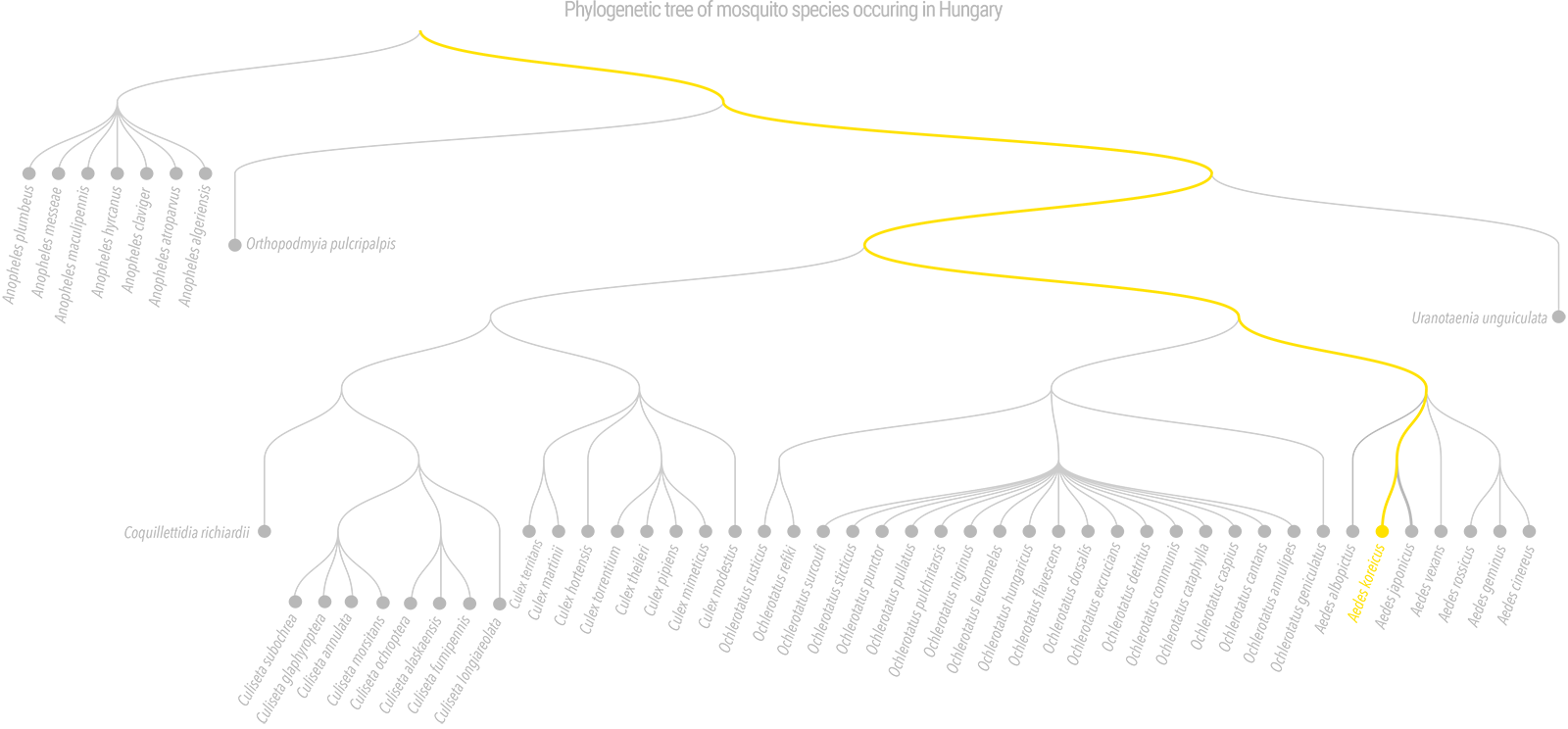

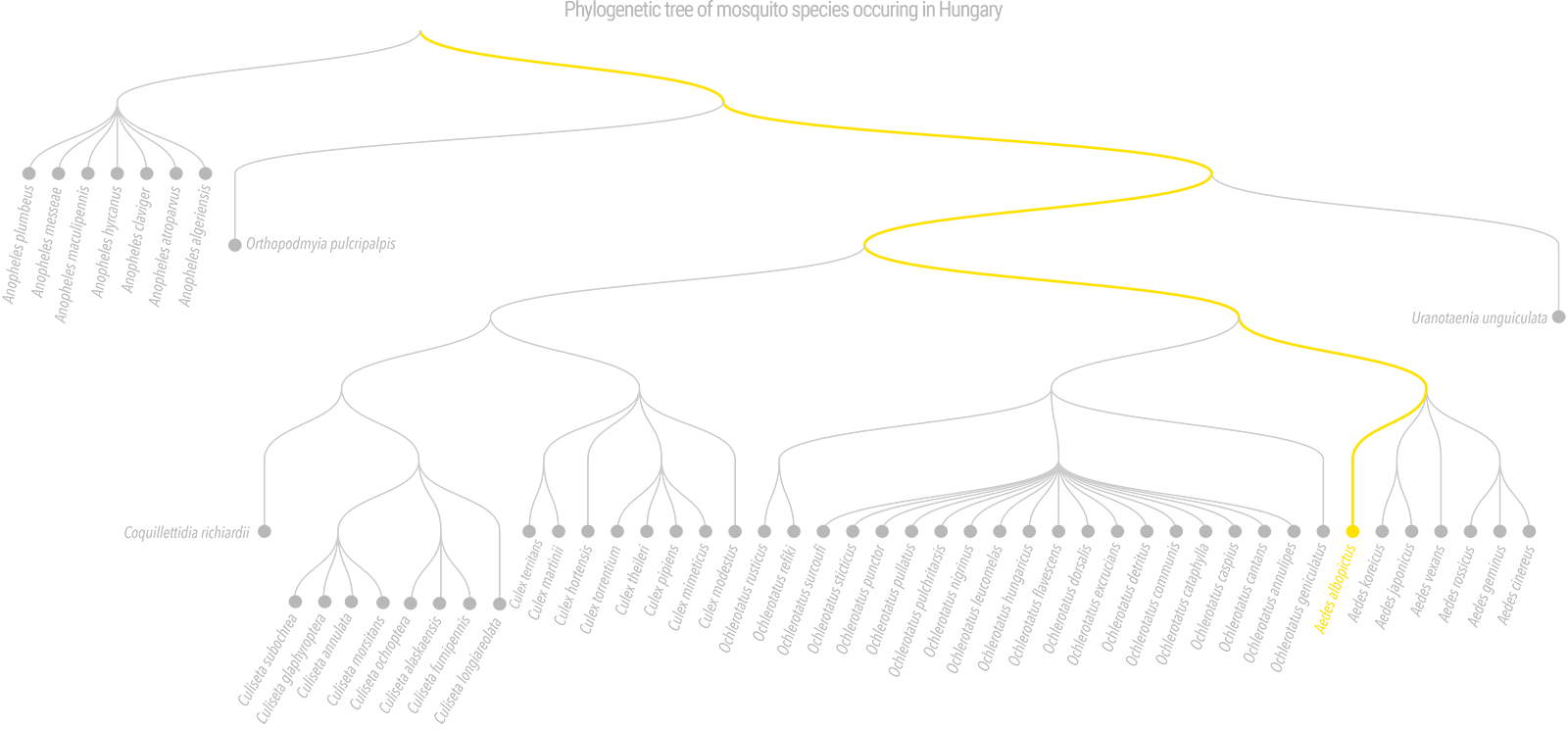

One of the four so-called ‘big insect orders’, to which most species belong, is the order Diptera. Insects are characterised by a body divided into three parts (head, thorax, abdomen) and three pairs of legs extending from the thorax when fully grown. Diptera – flies and mosquitoes – are easily recognisable by the fact that they have only one pair of wings (the second pair is reduced to so-called halteres). Species of the family Culicidae (mosquitoes) are characterised by a proboscis much longer than the head, and scales on the wings and body. There are about 6 500 species of the dipteran order so far recorded in Hungary. Slightly more than half of these are called mosquitoes of some kind. Within the family of biting mosquitoes, 50 native and 3 alien species have been identified in Hungary.

ASIAN BUSH MOSQUITO

Characteristics

The adult Asian bush mosquitoes (Aedes japonicus) are bigger bodied mosquitoes than the tiger mosquitoes or the korean bush mosquitoes; they are 6 mm long. Their body is black decorated with light and dark brown scales. Compared to the other two invasive mosquito species, the Asian bush mosquito has lighter coloration and less contrast. Its thorax bears five yellow stripes on the dorsal side, with the two closest to the longitudinal axis being particularly striking. (The pattern is similar to that of the Korean mosquito , differing only in that the two parallel stripes closer to the longitudinal axis are thicker and longer. The second difference is in the last metatarsal joint of the third leg, which is completely black in the Asian bush mosquito, while it presents characteristic white ring-like patches in the Korean mosquito.) Both sides of the abdomen display patches of white scales. The legs are black with white rings on them, but the last foot joint of the third leg misses the white ring. The eggs are 0,5 mm long, black, shaped like a cigar; the larvae have a brownish yellow coloration.

Distribution, origin

Like most invasive mosquitoes, the Asian bush mosquito spread to Europe thanks to globalization, tourism, and trade. It was first reported on the continent in 2000 in Normandy, in northwestern France, from where it spread further through the transport of tires. It was identified in Belgium in 2002; later, in 2008, larvae and adult specimens were found in the country as part of the Belgian national mosquito monitoring program. In the same year, the species appeared in Switzerland. It was then detected in southern Germany in 2011 and in northwestern Germany in 2012 thanks to German mosquito monitoring. Shortly afterwards, its appearance was also reported in the Netherlands, and since then it has appeared in other countries: Austria, Slovenia, Croatia and Spain. In Hungary, the species was first reported in 2012 on the Slovenian-Hungarian border; it then spread mainly in western Hungary, and between 2017 and 2018, large numbers were collected around Lake Balaton. Today, it can be found in most parts of the country.

Ecology

The eggs of the Asian bush mosquito are extremely resistant, able to withstand freezing and dehydration. This ability allows the species to appear anywhere as soon as the weather improves. However, they cannot tolerate temperatures above 30°C – in such heat, the individuals are unable to develop, which may be a limiting factor for the future spread of the species. In its native habitat – northern Japan – and in Europe, it overwinters as eggs. The eggs are resistant – they remain viable for a long time, even years, waiting for stagnant water at the right temperature to cover them, at which point they activate and begin to develop. The larvae develop in both natural and artificial waters, requiring only a few liters or less of stagnant water to create a breeding site. In their native habitat, they develop in tree hollows, but in urban environments they can breed in tires, birdbaths, cemetery gravestones, rainwater collection tanks, barrels and watering cans, buckets, or even milk cartons. As soon as the larvae hatch from the eggs, they immediately begin to feed. Their food consists of organic debris, bacteria, and single-celled organisms. In its natural habitat, the Asian bush mosquito remains active until late autumn, with many generations developing in a single year, which is probably also true of the Hungarian population. The adults are active during the day and aggressively attack humans, even inside homes, but they also readily feed on the blood of other mammals.

Transmitted diseases

Among the viruses transmitted by insects, it is capable of spreading West Nile virus, which has caused epidemics in America. It has been tested in numerous laboratories, and is capable of transmitting Japanese encephalitis virus, chikungunya virus, Rift Valley fever virus, yellow fever virus, and dengue fever virus.

KOREAN BUSH MOSQUITO

Characteristics

The body of the Korean bush mosquito (Aedes koreicus) is brownish, with legs that are black and white striped, similar to those of the tiger mosquito, and the thorax bears yellowish-golden stripes. The Korean bush mosquito closely resembles the Asian bush mosquito, but differs slightly in thorax pattern and the number of leg stripes. Alongside the yellowish or golden central line on the thorax, the Korean bush mosquito has two shorter secondary lines, whereas in the Asian bush mosquito these lines are longer (tiger mosquitoes, by contrast, have only a single white thoracic stripe). Additionally, the last segment of the third leg in Korean mosquitoes has a white stripe, giving them a more contrasting appearance. Their eggs are very similar to those of tiger mosquitoes but are slightly narrower and longer in shape.

Distribution, origin

The Korean mosquito (Aedes koreicus) is native to Asia, with its original distribution limited to Japan, South Korea, northeastern China, and eastern Russia. The species first appeared in Europe in 2008 in Belgium, where it quickly became established. It subsequently appeared in several other European countries, including Hungary, and spread across the continent in an increasingly large area: in Italy in 2011, in Switzerland, Slovenia, western Russia, and the Black Sea coast in 2013, in Germany and Hungary in 2016, and on the Crimean Peninsula in 2018. In Hungary, a few specimens belonging to the Korean mosquito species were first caught in Baranya County in 2016, but since then it became established in several places in the country (Tolna County, Budapest and its surroundings).

Ecology

Like most Aedes species, Korean mosquitoes survive the cold winter months in egg form, and as soon as environmental conditions become favorable for the species in early spring, as early as March, the eggs begin to develop. Adult mosquitoes can remain active until late autumn, even until the end of October. Currently, very little is known about the habits and requirements of this species; however, unlike native mosquitoes, they are active and bite not only in the evening but also during the day. In addition, the Korean mosquito is less sensitive to cold and drought and is better able to adapt to urban environments. Widespread in cities, it prefers to bite humans, but also feeds on other warm-blooded animals. It lays its eggs primarily in dark rock cavities filled with water and on the inner walls of tree hollows (a so-called container-preferring species), but in urban environments, any similar object or artificial element that can collect rainwater (e.g., garden ponds, construction debris, garbage, abandoned tires) serves as a suitable place for laying eggs and then for the larvae to develop.

Spread diseases

The role of the species in the spread of diseases is still unclear in many cases. In its original range in Asia, it is a potential carrier of the virus that causes Japanese encephalitis, as well as the Brugia malayi parasitic nematode, which causes elephantiasis, a disease involving the obstruction of lymph vessels (we do not need to worry about these pathogens in Europe at present). It has been confirmed under experimental conditions that the species is capable of spreading the nematodes Dirofilaria immitis and Dirofilaria repens, which are responsible for heartworm and skinworm infections in dogs and pose a serious animal health risk throughout Europe, including Hungary. In addition, it is also known as a vector for the chikungunya virus, which has caused several epidemics in Italy and France after being introduced into Europe.

TIGER MOSQUITO

Characteristics

The tiger mosquito (Aedes albopictus) is relatively easy to distinguish from other biting mosquitoes in Hungary, as this species has a very contrasting colouring: snow-white or silvery scales on a black background, with spots and stripes on both the body and legs. There are no other black and white mosquitoes in our country with such a contrast, except the ornate mosquito (Ochlerotatus geniculatus), which has a similar body colour but no white rings on its legs. The main distinguishing feature of the adults is a single white stripe running down the back of the thorax. It is smaller in body size than the native species, with a body length of only 5 mm. The eggs are about 1 mm long and dark brown or black in colour. Males are easily distinguishable from females because males have tufted antennae, while females have simpler, thinner antennae. It is also easily distinguishable from other invasive mosquito species, as the Korean mosquito (Aedes koreicus) and Asian bush mosquito (Aedes japonicus) have a yellow pattern on the thorax.

Distribution, Origin

The Asian tiger mosquito is native to Southeast Asia, but over the past three decades it has spread throughout most of the world, through intensive commercial and tourist activity, and passive transport. Its cold- and drought-tolerant eggs can travel long distances in used tires or in the water of lucky bamboo plants, which is how the species reached the Netherlands and California. By the time it was first detected in Italy, it had already spread throughout almost the entire country (except for areas at least 600 meters above sea level), and Italy became the most infected country in Europe. The mosquito was reported in France in 1999 and in Belgium in 2000, and has since become established in most European countries: France, Spain, Portugal, Belgium, Germany, Malta, Cyprus, Switzerland, Austria, Slovenia, Slovakia, Croatia, Greece, Bosnia and Herzegovina, Bulgaria, Georgia, Romania, Serbia, Montenegro, Albania, Moldavia, Monaco, North Macedonia. However, it has been introduced in some other countries but did not permanently establish, probably due to cold winters. In the Netherlands, for example, it can only survive the winter in greenhouses. Our first data from Hungary dates back to 2014, from near Baja. In the following years, it was found on the southwestern border and became increasingly common throughout the country.

Ecology

Tropical and subtropical populations are active throughout the year, without a dormant (diapause) phase. Populations living in temperate climates are influenced by temperature and day length. Eggs laid in late summer or early autumn do not hatch due to the short daylight hours. The species’ ability to hibernate allows it to overwinter in temperate regions, which contributes to its spread in Europe. The species’ adaptability is well illustrated by the fact that European specimens have been shown to be able to survive temperatures as low as -10°C, while the eggs of tropical specimens were destroyed at temperatures below -2°C. Adult animals (imagoes) in Italian populations have adapted to the cold and thus remain active throughout the winter. To lay her eggs, the female looks for a body of water that is not in contact with the ground – this could be water collected in a tree hollow or rock cavity, but it could also be water collected in rubbish discarded by humans or in a barrel exposed to rainwater. She lays her eggs above the surface of the water, on the side of the container or cavity, and they hatch when the water level rises due to precipitation and reaches the level of the eggs.

The Asian tiger mosquito is opportunistic in its feeding habits, meaning that it likes the blood of humans, domestic and wild animals, including reptiles, birds, and amphibians. However, laboratory tests and blood analyses show that it prefers human blood.

Transmitted diseases

Since it actively bites both humans and animals, it can play a significant role in the transmission of pathogens from animals to humans. To date, 22 types of arboviruses (insect-borne viruses) have been isolated from this species in laboratories. Of these, the most significant from a human health perspective are dengue fever, also known as breakbone fever, yellow fever, West Nile virus, and Japanese encephalitis virus. During the 2006–2007 chikungunya epidemic in Italy, the Asian tiger mosquito was identified as one of the vectors of the epidemic. The species is also a potential vector for the Zika virus; however, it is not only known as a vector for viruses, but also for nematodes, and is therefore capable of spreading heartworm and skinworm infections in dogs and cats.

THE BENEFITS AND HARMS OF CHEMICAL MOSQUITO CONTROL

Today, most towns in Hungary try to keep mosquito populations under control through chemical extermination. This means that at dusk, a truck sprays a poison that kills any small arthropods that come into direct contact with it. From this description, two serious disadvantages of this method are apparent.

The first is that it only kills the mosquitoes it “hits,” i.e., it does not kill those resting in dense thickets, nor those that will hatch from their larvae the next day. The second is that it does not discriminate between victims, killing or seriously poisoning non-target arthropods as well. In addition, in large quantities, the active ingredient is harmful to vertebrates and humans. Overall, although chemical mosquito control is an effective method, it is extremely harmful to the natural environment, which is why conservationists have long recommended using biological mosquito control methods whenever possible.

What is biological mosquito control and how does it work?

The active ingredient in biological mosquito control products commercially available in Hungary is a protein produced by a bacterium (abbreviated as Bti). This protein begins to exert its toxic effect in the digestive system of mosquito larvae. The use of Bti is much more environmentally friendly because it is orders of magnitude more selective than chemical pesticides. Although it is not true that it kills only mosquito larvae, the number of species unnecessarily poisoned is dwarfed by the victims of chemical pesticides. However, Bti is only effective against individuals that are in the appropriate larval stage at the time of application, so unfortunately, this method does not have a very long-term effect either. In addition, its application requires greater care and expertise: all breeding sites where the target species occur must be mapped, it must be determined whether the mosquito larvae are at the appropriate stage of development, and this must be repeated several times during the season. However, the method has another undeniable advantage, as it can also be used in private households: commercially available biological pesticides can be used in rainwater collection barrels, small garden ponds, and ditches.

There is another method of biological control that we rarely think of when we hear the term “mosquito control.” This is the protection of animals that consume mosquitoes. First and foremost, we should think of bats and birds, for whom mosquitoes are a very important food source. If for no other reason, it is worth installing birdhouses and bat boxes in our gardens, leaving a small patch of scrub in the corner of the garden, and welcoming smaller mosquito predators such as spiders and frogs.

Last but not least, each and every one of us can do a lot to reduce mosquito populations by paying attention to the water around our homes: Every 1-2 days, pour out any water standing in sandboxes, tarpaulin folds, and flower pots to prevent the formation of “home-grown” mosquitoes. This is also a way to protect against the invasive biting mosquitoes that are spreading in our country, which typically live close to humans and develop in stagnant water around the house. In addition, since mosquitoes are very poor flyers, this kind of local defense can make a big difference!